by Rayle Blevins-Odle, Regenerative Bison Project Manager at Mad Agriculture

As a young choctaw girl I grew up between two worlds. On one side, a lineage of land stewardship grounded in Indigenous ecological relationships where I was told stories about Grandfather trees and how Spider taught us to weave baskets; on the other, a system shaped by Western settler-colonial notions of fear and control that told me dandelions were weeds and spiders were pests. Today, I manage a bison restoration project for the Cheyenne and Arapaho nation in the Southern Plains, where the language we use daily—about animals, land, and productivity—carries deep consequences. This piece emerges from that dual perspective: informed by both formal ecology and ancestral knowledge. It’s also rooted in the work we’re doing at Mad Agriculture, where we believe that ecological transformation begins not just with practice, but with story.

At Mad Agriculture, we partner with farmers, ranchers, and Tribal nations to co-create regenerative management plans grounded in ecological health, economic viability, and cultural meaning. This includes grazing plans that restore native prairie function, market strategies that elevate values-based supply chains, and helping farmers and ranchers in their transition to holistic stewardship. Through this work, we regularly encounter how language—not just tools—drives decisions. Whether naming a plant “weed” or a species “nuisance,” the terminology often limits the imagination before any seed is planted or hoof hits the ground.

For farmers and regenerative land stewards, this means that success hinges not only on ecological literacy, but on narrative literacy as well. If we frame an opportunistic species as an indicator of imbalance rather than an invader, our management decisions can pivot toward restoration rather than eradication. Mad Agriculture incorporates this thinking into our work by using whole-farm diagnostics that consider the story the land is telling—whether it’s the emergence of certain plants, the presence of wildlife, or patterns in water retention. These observations guide management choices rooted in curiosity, resilience, and co-evolution rather than control and dominance.

As a society we have created a kind of narrative canon—an entrenched body of language shaped by media, literature, and everyday speech—that defines certain animals, plants, and insects as undesirable. This canon rarely reflects scientific truth as it ignores important ecological niches and is based in the settler-colonial idea that humans exist outside of the ecosystem, acting as enforcers of what is right and wrong. Entire industries are built on this canon and its disgust for certain beings: pest control, herbicide production, eradication campaigns. These are billion-dollar businesses that rely on vilifying species that happen to live alongside human infrastructure or challenge agricultural models. When we allow ourselves to be informed by this canon, when we inherit its assumptions without question, we step away from a holistic understanding of the land. We abandon the idea that every being has a role, a purpose, a place. Agricultural and ecosystem management techniques are not immune to the influences of this canon. If we are not careful, they can and will continue to enforce negative and inaccurate information to future generations of stewards, further distancing us from an interconnected landscape.

Yet the canon persists. And through it, we place ourselves on a throne passing judgment and handing out death sentences simply because a being doesn’t fit our aesthetic ideals or our narrow definitions of usefulness.

In agriculture, the consequences of this mindset are amplified. Management decisions begin with language. What’s a "crop," and what’s a "weed"? What’s “livestock,” and what’s a “nuisance”? These categories feel objective, but they’re shaped by power, by whose values are enshrined in policy and economics. Weed laws, for instance, aren’t neutral. They criminalize plants that don’t support monoculture. Milkweed, long labeled noxious in the Midwest, is the only host plant for monarch butterfly larvae. Its removal, under the guise of weed control, contributed directly to monarch population declines (The Xerces Society, 2017). Mesquite—a native tree that offers shade, erosion control, and forage–is framed as an invader in Texas and Oklahoma. Despite its deep cultural and ecological role, state-supported eradication programs treat it like a foreign threat (Briggs et al., 2005).

These are not just labels. They’re permission slips. When we call something a weed, we stop asking what it’s doing there. When we call something a pest, we skip the why and jump to the how—how do we remove it, neutralize it, kill it? But these terms didn’t emerge naturally. They’re part of a colonial legacy, a project that saw land as wild, empty, and underused. A project that classified, controlled, and eliminated that which didn’t serve its goals.

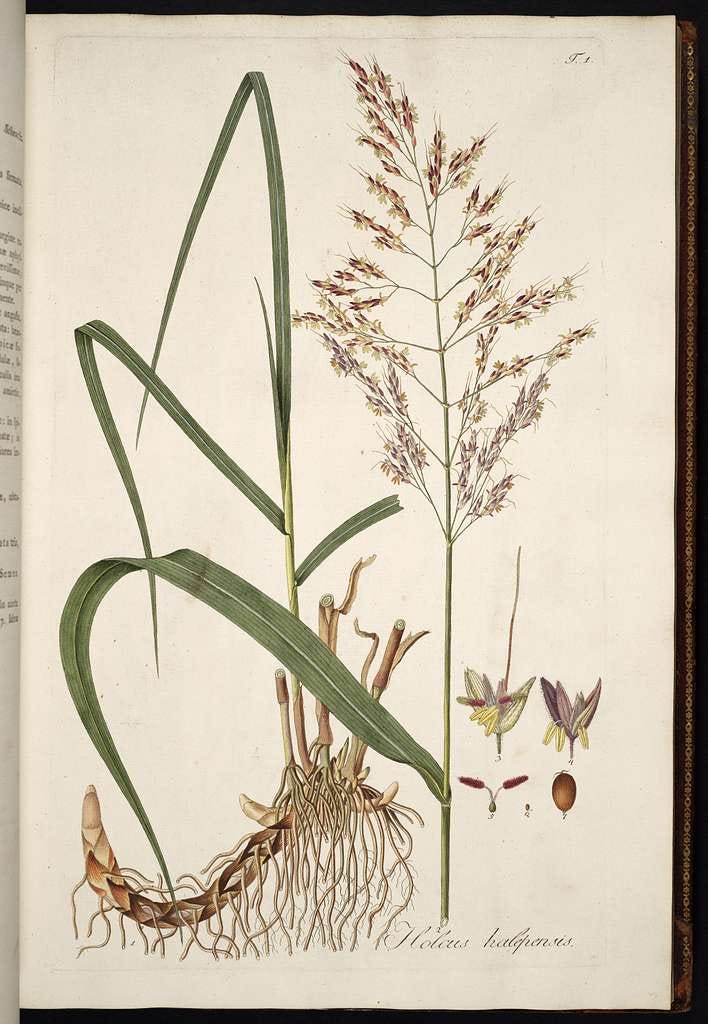

Take Johnson grass (Sorghum halepense), one of the most vilified plants in the American South and Great Plains. In Oklahoma, Texas, and across much of the Midwest, it’s listed as a noxious weed in a legal category that not only allows but mandates eradication efforts on public and private lands. Ranchers and farmers are often taught that Johnson grass “invades” pastures, “chokes out” native grasses, and “depletes” soil value. As a result, county weed boards and state agencies incentivize chemical spraying and aggressive tillage to eliminate it. But what’s often left unsaid is that Johnson grass thrives primarily in disturbed soils—those compacted by overgrazing, bare from drought, or repeatedly plowed for monoculture. It’s not causing the disturbance. It’s responding to it. Ecologically, Johnson grass has value. It provides ground cover that prevents erosion, biomass that can be grazed during drought, and carbon-capture capacity that rivals some native grasses. Its resilience is exactly why it shows up, yet the language used to describe it casts it as a threat, an invader, something unnatural and unworthy of understanding. This framing has direct management consequences. Instead of addressing overgrazing, poor soil structure, or lack of plant diversity, land managers are trained to declare war on the plant itself. The result? More chemical input, more bare ground, more ecological imbalance. It’s a closed loop of blame, driven by language.

Even bison, iconic and culturally central to Native nations, were systematically massacred under the guise of control of a dangerous and aggressive “vermin”, according to the canon created by the settler colonial powers of the time. We see the remnants of this narrative persist today as they are sometimes labeled “feral livestock” when they roam beyond fences, and some public factions still believe them to be a significant danger to other livestock through brucellosis—a disease transmitted only under rare circumstances, such as when cows consume bison placenta and afterbirth matter in situations of co-habitation. These outdated beliefs limit tribal jurisdiction and hinders ecological restoration efforts. All this, while we ignore the simple irony of judging a once-continent-roaming animal by their ability to stay within fencing lines.

Similarly, across much of the Southern Plains, prairie dogs are treated as a scourge. Ranchers and land managers frequently label them as “vermin,” “nuisance species,” or “forage competitors.” Extension offices and wildlife agencies often recommend poisoning or mechanical destruction of prairie dog towns to “reclaim” pasture land for livestock. The implication is clear: these animals are out of place and reducing the land’s value. But this view is shaped by a language of scarcity and control, not by ecological evidence or cultural memory. From an ecological standpoint, prairie dogs are a keystone species of the shortgrass prairie. Their burrowing and grazing activity stimulates plant regrowth, increases soil aeration, and improves nutrient cycling.

Prairie dogs and bison co-evolved in a disturbance-adapted system, highlighting a dynamic relationship that contrasts sharply with settler-colonial narratives of conflict and control. Yet management discourse continues to frame prairie dogs as problems to be eradicated, rather than participants in a complex system. In many Indigenous worldviews, prairie dogs are not pests but relatives and caretakers of the land with roles and responsibilities. Among the Lakota, for example, they are seen as part of the web of kinship, signaling change and maintaining balance. Some oral histories describe them as storytellers and watchers, observing the land and alerting others to shifts in the ecosystem.

Colonial power has always depended on naming. To define something as wild, invasive, or unproductive is to declare it disposable. Even the word “management” deserves examination. It implies authority, top-down control. In contrast, Indigenous knowledge systems often speak of “tending” or “relating to” the land. These words reflect mutual responsibility, not domination. Potawatomi scholar Kyle Whyte explains that settler colonialism alters ecological relationships by replacing them with systems of classification and extraction (Whyte, 2018). “Pest” is not just a label; it’s a reflection of a broken relationship.

What if we reframed these labels? Instead of “problem species,” we might say “opportunistic species.” Instead of “invasion,” we could talk about “imbalance” or “response.” These words invite observation, reflection, and humility. They let us ask: Why is this species thriving here? What story is it telling about the land? Kimmerer writes that in some Indigenous languages, the word for plant translates as “those who take care of us” (Kimmerer, 2013). That’s not just poetic but a call to responsibility, it reframes the ecosystem as a system of reciprocal care. Words don’t fix the land but they do shape how we act upon it. Language is land management—a “weed” invites a sprayer, a “relative” invites a ceremony, a “nuisance” gets trapped, a “teacher” gets watched, listened to. What would it mean to restore not just prairie grasses or bison herds but a vocabulary of respect? I'm not arguing that we abandon management altogether. Ecological pressures are real. But there’s a profound difference between responding with domination and responding with relationships.

Let’s stop asking, How do we get rid of this thing?

And start asking, Why is this thing here?

What is it teaching us?

What does a right relationship look like?

SUGGESTED READING

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. Braiding Sweetgrass. Milkweed Editions, 2013.

Whyte, Kyle. "Indigenous Climate Change Studies." Nature Climate Change, 2018.

Davidson, Ana D. et al. “Ecological Roles and Conservation Challenges of Social, Burrowing, Herbivorous Mammals in the World's Grasslands.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 2012.

Briggs, John M., et al. "An Ecosystem in Transition: Causes and Consequences of the Conversion of Mesic Grassland to Shrubland." BioScience, 2005.

Freese, Curt H., et al. Second Chance for the Plains Bison: Ecological Restoration and the American West. Island Press, 2007.